After arriving in Borneo and learning about dynamite fishing and sea turtle nest poaching, I was inspired to begin my month of volunteering at the Tropical Research and Conservation Center. Our daily schedule Tuesday through Saturday would include a morning work dive, followed by lunch, then an afternoon work dive and data entry, then dinner and a turtle walk. Some days there would be an option of a third or fourth fun dive if multiple people were interested. Sunday was just two fun dives and Monday was our day off.

Volunteers were assigned to different work dives which varied by location and task. Most dives were done on either the house reef or around the island but occasionally we would go to some of the neighboring islands and all dives were from the boat or the local dock. I was thankful that the distances for carrying the tanks and equipment were no more than 20 feet at a time. The work dives alternated between the following tasks:

Turtle ID and Health Surveys were conducted to track turtle movement and health over longer periods. Groups of three would include the dive leader/turtle spotter, photographer, and data collector. Once a turtle was seen, the photographer would take pictures of the turtle’s face, shell, and any other health indicators like barnacles, shell cracks/chips, tumors, etc., and the person with the underwater slate would record the data. Photos would then be used to identify the turtle based on facial patterns, and the information collected would go into a location and health database.

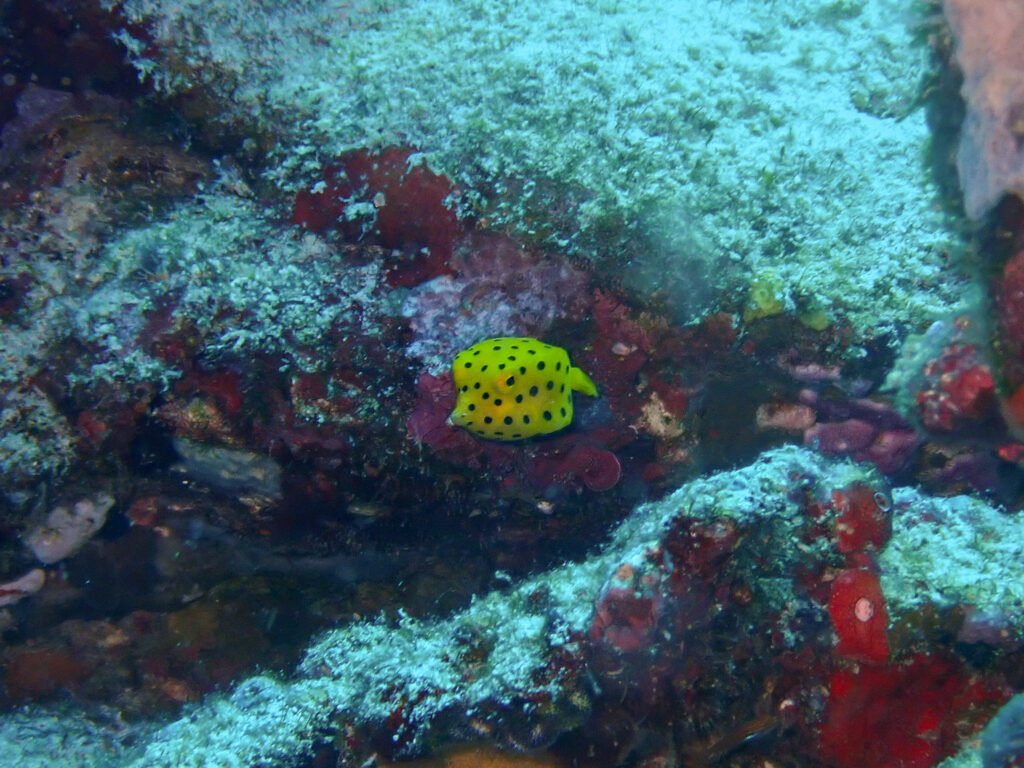

Fish Identification was done to track the abundance and biodiversity of the fish over time as the reef grew. A dive leader would keep track of timing and depth while one volunteer took pictures of a specific fish and the other would record data, then move on to the next fish. The data processing of these dives were the most difficult at first until I began learning the names and recognizing the different species.

Crown of Thorns (CoT) Removal was done whenever an outbreak was recorded. The CoT is a type of venomous, thorny starfish that eats coral polyps. Although it is native to this region, overfishing of its predators has left the population unchecked and eating away at the corals. Teams of two would set out with hooks to pull the CoT off the reef and carefully place it in a basket. If we collect more than 30 CoTs, they get dissected to weigh their reproductive organs, which are recorded in a database to better inform when to limit their spawning events.

Underwater Cleanup was done every week to remove old fishing lines from the dock areas on other islands. During COVID, travel amongst the islands was limited, causing residents to rely on fishing to feed themselves, even though it’s normally prohibited. As a result, thousands of feet of fishing lines and hooks have been caught and sacrificed to the reef.

Coral Planting was done at the artificial reef structures. Dive teams of three to five would either replant coral that had fallen or cut off small pieces of coral from an existing coral head. Coral was replanted on an artificial structure, normally comprised of concrete blocks or rebar, using super glue.

Coral Measuring was done every month to track coral growth from the plantings. Given its limited frequency, I didn’t participate in the measuring, but it sounded like the most difficult of the dives.

Artificial Reef Maintenance was done to clear debris and rubble from the artificial reefs. If left alone, algae and sand would take over the coral planting sites before new corals could propagate. We took brushes and carefully scrubbed between the new coral plantings, being careful to avoid any new growth.

After my first week at TRACC, it was easy to get into the dive routines and activities on land. Aside from the work being purposeful, each day underwater improved my skills as a diver. Practicing my buoyancy while carefully removing fishing lines from the reef or delicately holding on to a piece of coral and waiting for the glue to set was completely different from the type of swim-through diving I was used to. Plus we got a variety of conditions, some days the visibility was excellent with minimal current, and other days the current would rip, causing us to end the work early and just drift along.

Since the reef was still rebuilding, the diving wasn’t amazing but these low expectations made every dive unique and special. Around the full moon and new moon, there seemed to be an abundance of turtles on each dive and I counted over 30 on one dive! I loved doing the turtle surveys and having an excuse to get close to these massive creatures. After learning that only 1 in every 1,000 turtles hatched will make it to adulthood, I realized how incredibly special each turtle is, having defied many odds. My favorite was watching turtles scratch their bellies to remove barnacles, mimicking some kind of dance.

On top of the underwater work, we also did a beach cleanup at least once a week. When I first arrived, I couldn’t understand how a conservation group could have so much trash scattered about its shoreline. I soon realized that no matter how often the trash was removed from the beach, it would just show up again the next day with the high tide. Within 30 minutes, we could easily collect 10 large sacks of trash, mostly plastics and water bottles. It’s easy to become jaded to the sight of trash and it’s difficult to remember that picking up just one piece is still making a difference.

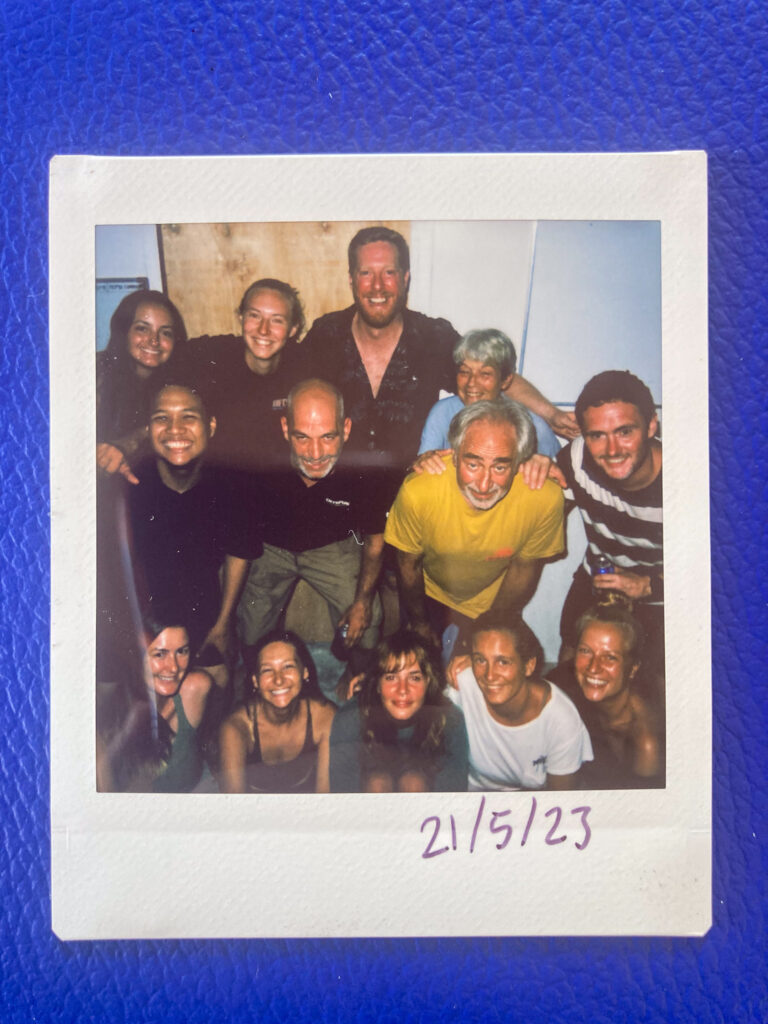

Being involved with TRACC felt great, to do something I love and for a purpose made me ponder ways I could be more involved in something like this from a career perspective. One of the other directors, Hazel, was visiting for a few days and had just submitted per Ph.D. thesis on work she is conducting on the island. To my surprise, she was researching slope stabilization techniques for coral rubble. Given the topography of the island, coral struggled to grow beyond any flat areas because it eventually fell down the slope to a depth where it could no longer survive. Pouring concrete to make more step reefs installed with rebar was expensive and using netting to stabilize the slope was just introducing more plastics into the ocean. So, her thesis would be to research and test out different techniques and materials. Hearing about civil engineering practices in marine restoration was inspiring and I hoped to keep finding ways that I could potentially be involved in something like this in the future.