After two weeks of pure bliss in Maupihaa, we finally had a small weather window with lighter winds for the sail to Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands. Eitan had been checking the weather every day, hoping for a break but it looked like the wind would only lighten up for a bit, then pick back up again without giving the seas any time to calm down. The extended forecast only looked worse and worse and we were starting to get low on provisions and fuel. One thing was certain: this trip was going to be uncomfortable.

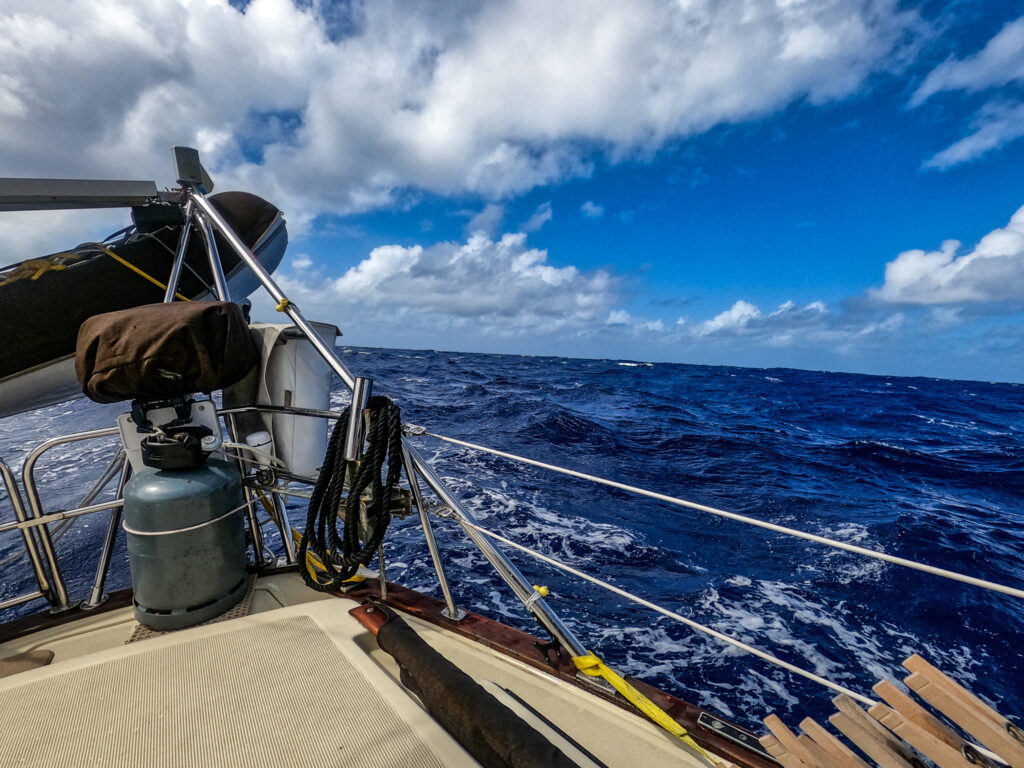

We stowed and secured everything inside and did one last scan around the decks to make sure everything would stay in place, then pulled the anchor and made our way through the pass. I insisted on putting up the isinglass to enclose the cockpit on the windward side, knowing we were likely to take some waves into the cockpit. Once outside of the atoll, the wind was already in the mid-20s and as we passed out of the lee of the island, the swell began throwing us back and forth. Eitan instructed Evan and me to keep an eye on the approaching sets and turn the boat downwind if we saw a big wave coming. With the wind and swell directly on the beam, we were at risk of getting knocked down… any sailor’s nightmare!

The trouble was that it was impossible to predict how the boat would react to the different wave sets. Depending on the wave period, the small waves had the potential to throw us over more than some of the big ones! I took the first 4-hour watch and held on as the boat fell to the trough between waves then got slammed by the next one, breaking over the bimini above me. Eitan, Evan, and I fell silent as we shared wide-eyed glances, getting a glimpse at what the next four days would be like.

Evan loaded up on seasickness medications before we left and his stomach seemed to be doing much better despite the worse conditions. This time, it was Eitan who was seasick and I watched from the cockpit as he rushed to the bathroom. We continued on with our 4-hour on, 8-hour off watch schedule, but every minute felt like an hour. The winds were sustaining around 30 knots, much more than we would ever choose to sail in. On the plus side, we were averaging above 6 knots of speed and making good time.

The V-berth was almost uninhabitable with all the movement, so Evan laid out some pillows next to the mast and tried to get some rest. Once again, the boat got thrown on its side resulting in a big crash. I got up to see what had fallen and it seemed the big toolbox (that had been tied down) broke free, jumped over the table and landed on Evan’s lower body! He was pinned down but luckily not hurt and I apologized profusely for what had happened as I helped to free him. I went through the cabins and salons once again, taking anything that wasn’t already strapped down and moving it to the shower.

During Evan’s watch, Eitan and I laid in our passage configuration, forming an X with our bodies in the bed, trying to brace each other from moving. I know Eitan had seen worse conditions than this on other boats but making his own boat go through it was soul-crushing for him. Even though SV Sierra Wind was handling it much better than I would have expected, these conditions were hard on her. For passage making, Eitan will always error on the side of comfort, even if it means motoring because it’s much easier on the boat and things are less likely to break.

Eitan and I lay there in silence and I asked what was on his mind. Hesitantly, he shared a message he received from our other friends who were off sailing in the same conditions. He said they had gotten hit by a few fast-moving squalls with wind speeds into the 50s, seemingly out of nowhere. Yikes! If it was happening to them, it could happen to us! For the rest of the trip, I kept my eyes glued to the radar for any sign of a system approach.

Even though I prepared enough food for the passage, I found myself too anxious to eat. I hardly drank any water for fear that I would need to pee during my watch, leaving the helm unmanned during an autopilot failure. In an effort to get some sustenance, I drank a little coconut water and snacked on chunks of coconut but quickly ran to the bathroom, throwing it back up.

Conditions persisted as we counted down the minutes and miles. I spent my watch looking upwind at the approaching swell. I was too scared to look toward the other side of the boat as we heeled above 45 degrees, knowing the toe rail and lifelines were being submerged. Eitan said he saw the water come almost up to the cockpit coaming, sending water down the air intake for the engine.

I thought back to our time during the Pacific crossing when we got so much salt water into the freshwater tank vent that it contaminated all of our water. I remembered to tape up the water tank vent but my stomach sank as I realized we were probably getting salt water into the diesel tank! Not knowing much about engines, I anxiously thought of all the things that could go wrong. Is our fuel tank contaminated? What if we destroy the engine with salt water? Since there are no anchorages in Rarotonga, how will we be able to maneuver into the harbor? Eventually, I learned what an oil/water separator was and that this wasn’t much of an issue.

By day three, and for the first time during this passage, we saw the wind speeds drop below 20 knots, and the next day we could finally see the outline of Rarotonga. There’s no feeling like dropping the anchor or tying up to a dock after a long passage but it seemed like our struggles weren’t over yet. In all of the Cook Islands, the only place you could take a personal yacht was the harbor in Rarotonga. As we approached the entrance in the late afternoon, I saw the harbor completely exposed to the north, allowing much of the surge to enter. It seems our place of refuge would still be quite rollie.

The harbor, also, didn’t have any floating docks and to secure the boat, we needed to drop the anchor and back up to a concrete wall, then throw the stern lines to be tied onshore. We did as the harbor master instructed and after two attempts, we were secured to the wall. Even though we were ready to sleep for the next 24 hours, customs and immigration officials began congregating on the dock waiting for Eitan to pick them up in the dinghy.

Once onboard, they began the check-in process and we presented all of our forms. These people looked Polynesian but spoke English with a New Zealand accent. Wow, was it nice to speak English again! About 45 minutes later, the paperwork was complete and we were presented with a bill that included a fee to compensate them for working overtime, given that we had arrived at 5 pm. Since we had come from the nearest land mass, over 400 miles away, they didn’t seem to understand that we had tried to get there as fast as possible and scolded us for arriving past closing hours. Well… welcome to Rarotonga!