Do you ever feel like things line up so perfectly, that you couldn’t have planned it better yourself? That’s exactly how I felt about my time at Tevena House Reef. If you remember a few blogs ago, everything about this place felt like a manifestation becoming more and more true. When I first met the GaiaOne team at the Malaysian Dive Expo earlier in the year, I thought the 4-week coral restoration course was a regular course they offered every month. It wasn’t until I arrived that I realized the October course was the first and only time they were offering the course that year. Not to mention getting to participate in the freediving retreat the week before, followed by the Sounds for the Ocean concert. To top it off, the founder of Ocean Gardener, the organization that created the course content, would be there to teach some of the advanced coral courses.

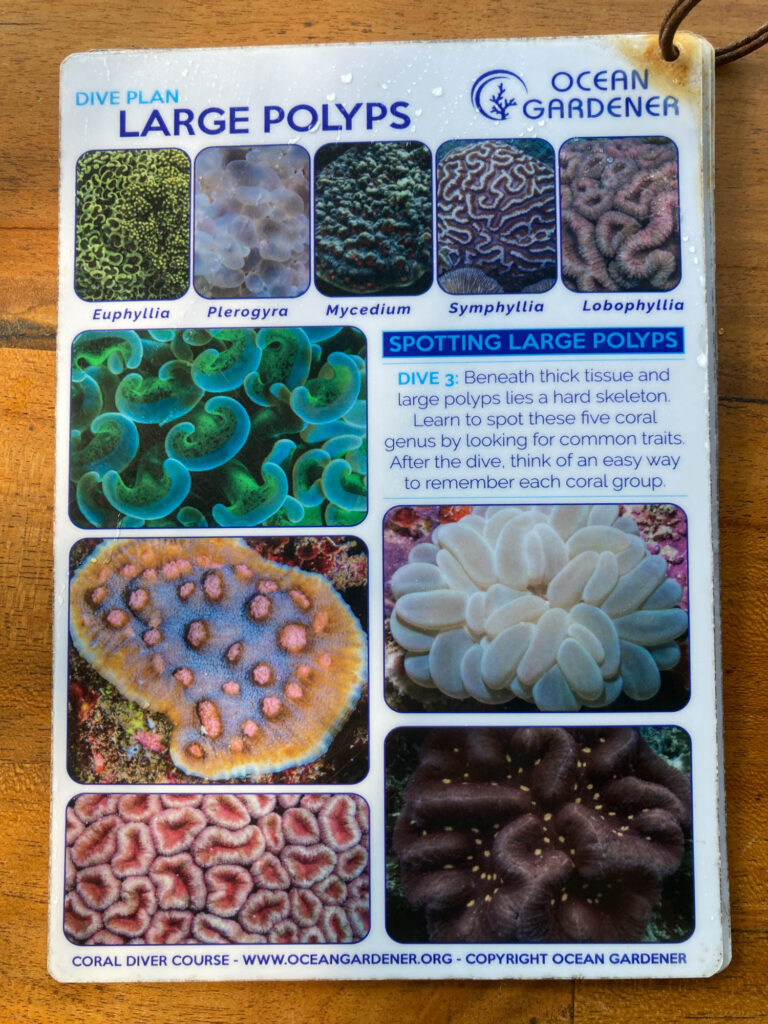

I was just one of three students in the course. The other girls included Stephanie, from Switzerland, and Lesia, from Spain. Our local teachers for the course were Angger, an Indonesian woman leading their local coral restoration effort, and Marco, from Italy, who ran the diving operations and assisted with restoration. For the first few days, we started with a lecture in the morning, followed by one or two dives in the afternoon, depending on the tides. During the lecture, we learned about the different types of coral and how to identify them followed by some videos explaining more in-depth topics like growth forms, reproduction, predation, and disease. During the dives, we would take our coral identification slates and try to identify which corals we learned about that day.

After the first few days of the course, Vincent, the founder of Ocean Gardener, arrived to teach the classes in person and share his experience growing coral in Bali over the last 20 years. It was great to have someone to answer the toughest questions I could come up with and just general curiosities about reef fish. I asked him about the outlook of the world’s corals given the climate situation and he believed the future of corals existed in aquariums. Between warming seas, pollution, overfishing, and degrading water quality their only hope was to exist in captivity.

I also asked him about the potential of making a career transition to marine conservation and reef restoration and he quickly crushed that dream. Unless I was willing to go back to school for a master’s and Ph.D., graduating top of my class, any real career opportunities were limited. Anything that I could learn to do, outside of research and academia, should be taught to a local person instead. Rightfully so, any coral restoration jobs and training should go to the local people for them to better understand and manage their marine resources. As an American, I am expensive to hire (not to mention the work visa), I don’t speak the language, and I don’t have a long-term future in the region. Vincent explained the best thing I could do would be to secure an income elsewhere and treat coral planting as a hobby and volunteer opportunity, never expecting an income.

Once we learned the basics of which coral was which and how to assess reef health, we began learning the different planting techniques. Coral fragments are collected throughout the reef, often just loose pieces broken off from the mother colony from swell, turtles, or other impact. Then we went about planting the fragments in little colonies around the reef, hoping for the small pieces of the same species to grow together. We used premixed bags of water and cement in a toothpaste consistency then looked for dead areas of reef or rock to secure the fragments to. This is the best of the planting methods because, once you’re done, you can hardly tell it was planted, blending in with the natural environment. Plus, it doesn’t have any artificial structure, susceptible to degradation over time and requires no ongoing maintenance.

The next method we learned was using coral spiders, hexagonal structures welded out of rebar. The structures are placed in a flat area, sometimes sandy, and not suitable for direct planting into the reef. We used plastic zip ties to secure the coral fragments to the structure which will eventually begin growing onto the rebar. We also tried using cotton string and metal ties to secure the fragments but the coral didn’t seem to like these alternatives as much.

We also learned a rope planting method, used to establish reefs in areas taken over by sand and loose substrate. The rebar is hammered into the ground, marking the four corners of a square. Then, coral fragments are woven into the rope and secured to the rebar, suspended above the bottom. Eventually, the corals will grow heavy and settle on the bottom but the suspension keeps them out of the way of predators and out of the sand.

The last method we learned was the cookie and transplanting method. First, we cast mushroom-shaped concrete cookies and then placed them into an underwater nursery rack. Then, we plant small coral fragments using concrete on each of the cookies. The little corals sit in the nursery, protected and maintained for a year until they are big enough to be transplanted into the reef, much like to direct planting method.

Finally, we learned to assess reef health and manage coral predation. The coral in this region has two main predators, the drupella snail, and Crown-of-Thorns starfish, both suck polyps out of the coral, leaving a white exoskeleton. They typically eat fast-growing corals, and in a balanced ecosystem, help to increase the biodiversity of corals by making room for slower-growing corals to populate. Unfortunately, their natural predators have been overfished and the populations are out of balance. One of the Crown-of-Thorns starfish predators is the triton snail. Unfortunately, they are also harvested for their massive, foot-long shells. You often see them being sold in town, for just a couple of dollars, to tourists not knowing that this action has detrimental impacts on the reef. We collected both the coral predators regularly.

It was a jam-packed month of diving and coral restoration and I was incredibly grateful for the stars aligning for me to be there at that time. Now that the coral restoration course was done, I would be sticking around for another couple of weeks to keep planting coral!

Making a small and indirect contribution to coral restoration through you! Please keep it up for as long as it makes you happy.